As we head back to school this year, science-based best practices in education will of course be top of mind. Science of Reading discussions often focus on classroom instruction, teacher education, and curricular resources—all of which are vital factors in literacy development. But when it comes to learning to read, nothing is more important than a reading-ready brain.

Unfortunately, we are not born “ready to read.” This is because reading is a relatively new phenomenon. It wasn’t until after the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s that large populations of people across many countries began to read (Sedita 2020). In contrast, the human brain has had years to acclimate to spoken language. While the precise date of development has been debated, with experts tracing its genesis anywhere from 200,000 to 27 million years ago (The Atlantic 2019), our brains have evolved in ways that allow us to express and process language with relative ease. As a result, most young children learn to speak quickly and without effort or formal teaching. In other words, oral language develops naturally.

Reading is not a natural process. Speaking to a child typically ensures that they will learn to talk but reading to a child—while important—will not alone yield a fluent reader (Seidenberg 2017). Instead, reading requires explicit, systematic, and cumulative instruction (Castles, Rastle, & Nation 2018; Gough & Hillinger 1980; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [NICHD] 2000; Seidenberg 2017 ). This instruction builds connections between certain areas of the brain—connections that are vital to reading.

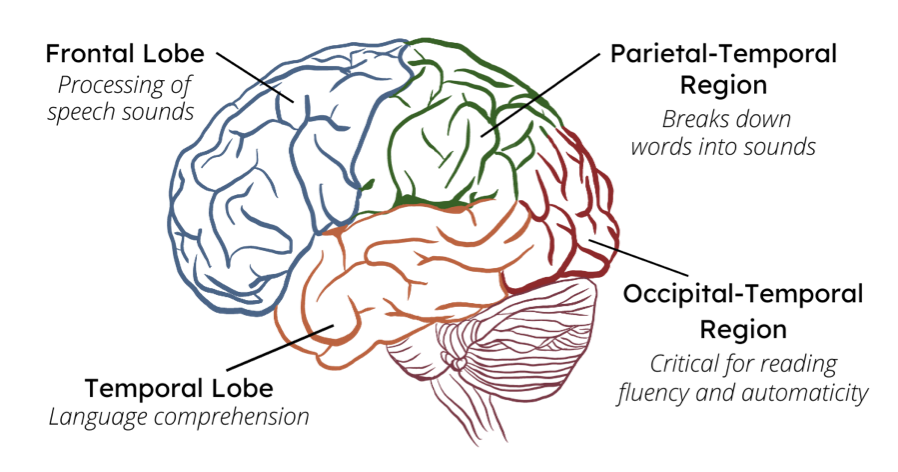

According to the Science of Reading, there is no one area of the brain that is solely responsible for reading—it requires a great deal of collaboration. The parietal-temporal region enables a reader to break down words into sounds while the temporal lobe is responsible for language comprehension. The occipital-temporal region is critical for reading fluency and automaticity. The frontal lobe controls the processing of speech sounds. While all of these areas are engaged during reading, their exact levels of engagement vary, depending on a person’s reading ability. Drs. Anne Cunningham and David Rose note that “. . . beginning readers show more activity in the parietal-temporal region while more experienced readers become increasingly active in the occipital-temporal region.”